Sanders is Strongest General Election Candidate: Crushing Trump 53% to 38%

9 2016

The Vermont Senator is poised to arrive at the Democratic convention as the stronger candidate to take on Trump.

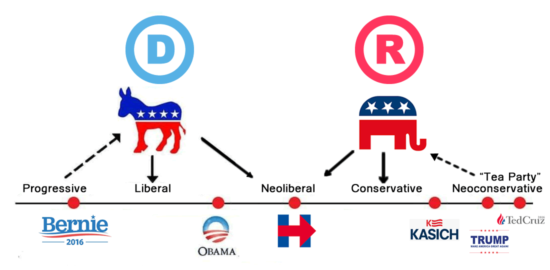

Senator Bernie Sanders would defeat Donald Trump relatively easily in a general election, according to the latest polls. An average of the three most recent major polls predicts a victory of more than 14 points, which would be a landslide in modern presidential politics.

- CNN/ORC, May 1: Sanders obliterates Trump by 16 points

- IBD/TIPP, April 28: Sanders defeats Trump by 12 points

- USA Today/Suffolk, April 24: Sanders defeats Trump by 15 points

As the country adjusts to the notion that a xenophobic, racist billionaire will be the Republican candidate for the presidency in November, no doubt many hope the strongest candidate emerges from the Democratic Party to defeat him.

The polls are clear on who that candidate is.

And at this point, it isn’t just (more…)

Be the first to comment >

Posted in Peaceful Revolution | Politics

by Tony Brasunas on May 9, 2016

Connect & Share